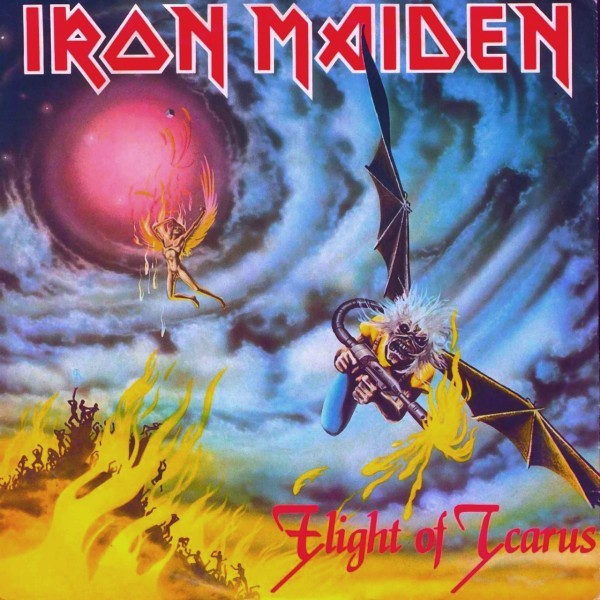

“Flight of Icarus” (1983) * Written by Adrian Smith and Bruce Dickinson * Produced by Martin Birch * 45: “Flight of Icarus” / “I’ve Got the Fire” * LP: Piece of Mind * Label: EMI (UK) / Capitol (USA) * Charts: UK (#11); Billboard Rock (#8)

A few things about Iron Maiden’s 1983 “Flight to Icarus”: It was the UK metal institution’s highest charting track in the US (#8 on the Billboard rock charts); its ending features an irrefutable demonstration of metal vocal majesty; and it found disfavor with band captain Steve Harris, who resented singer Bruce Dickinson’s insistence on keeping the tempo out of the full gallop zone. He thus banged his gavel and forbade live performances of it for the span of thirty-two years. Another thing: it uses the monotonous metal chord changes of Im-VIIb-IV in a way that doesn’t sound monotonous, and gives an alternate treatment of the Greek myth of Icarus, in which the hero’s journey to the sun is a teenage rebel’s willful self-destruction. Although the lyrics do leave room for interpretation, Dickinson made his intended meaning clear in his 2017 What Does This Button Do autobiography.

What other pop songs have an Icarus theme? Duncan Browne’s “Death of Neil” and Scott Walker’s “Plastic Palace People,” both from 1968, come to mind as the best ones worth mentioning, each of them fairly ambiguous tales about boys with wings and both of them clearly tragic. The B-side of “Flight of Icarus” is a worthwhile, thematically consistent non-album cover of Montrose’s 1974 “I Got the Fire.” (You can hear the genesis of the “Icarus” chorus melody in “April” by Dickinson’s heroes Deep Purple.)