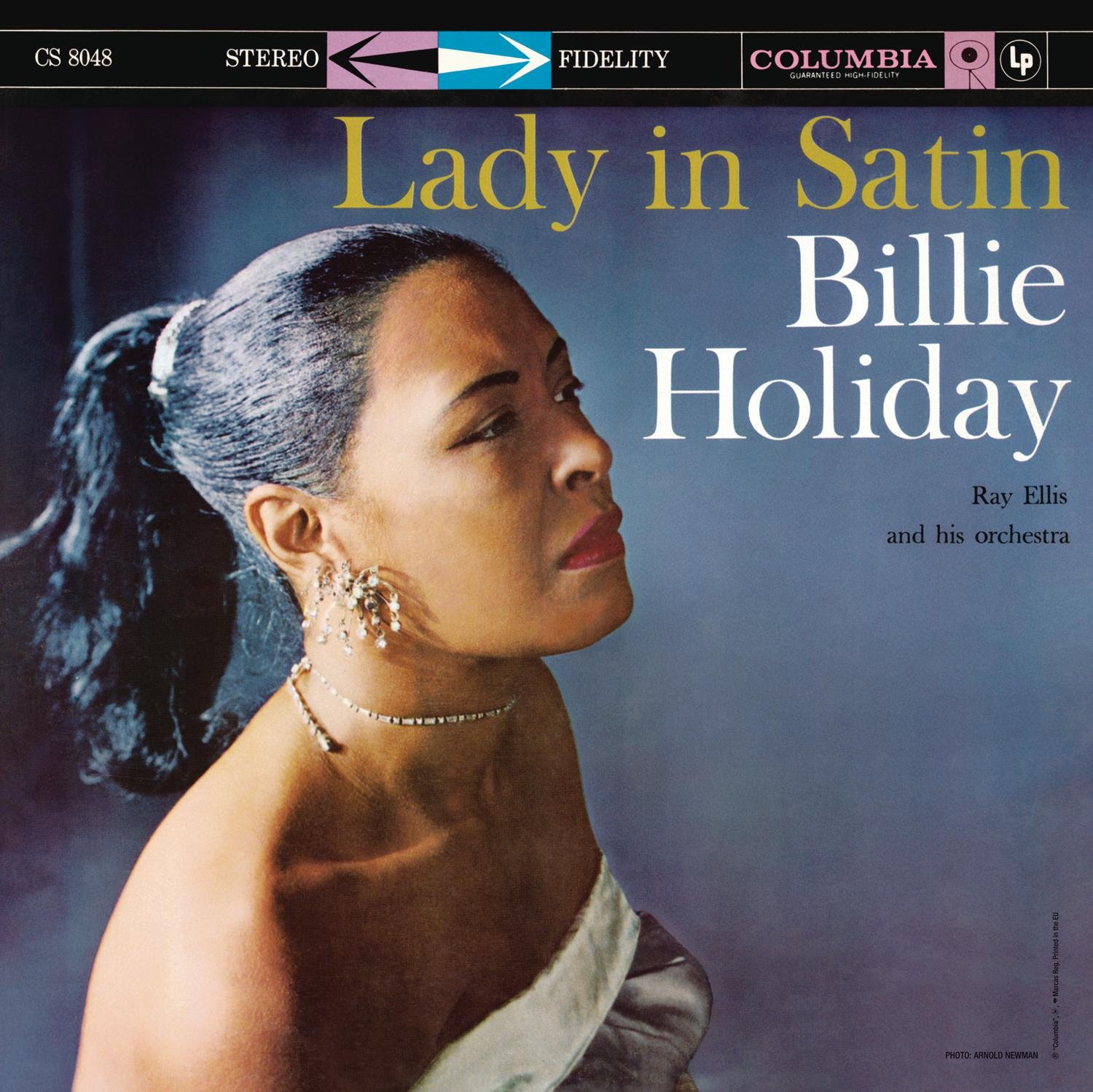

“You’ve Changed” (1958) – Billie Holiday * Written by Bill Carey and Carl T. Fischer * Produced by Irving Townsend * Arranged by Ray Ellis * LP : Lady in Satin * Label: Columbia

For a worthwhile overview of the stardust-sprinkled wonder that is Billie Holiday’s Lady in Satin album, read Will Frielander’s entry in his book The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums (2017). This gives a refresher on the lifetime of personal pain she brought to the sessions, and also her unlikely pairing with Ray Ellis, whose own artistic banner as a studio sugar man waved considerably lower than Holiday’s.

One track on the album emerges with special glory halfway through and stops listeners in their tracks. This is “You’ve Changed,” and although others had previously dampened it with their tears, Holiday transforms it, with her peerless control and inflections, into something that seethes and devastates.

And why does this lament about a love interest who has become woefully incompatible manage to jibe so well with its angel choirs and galactic backdrop? Because it has a secret message of hope, a subliminal flip side of meaning that taps into one of humanity’s fondest anticipations that people can, indeed, change.