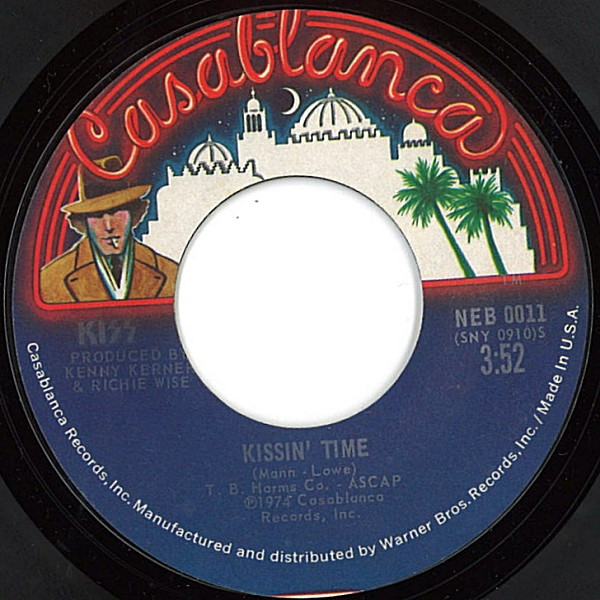

“Kissin’ Time” (1974) – Kiss * Written by Bernie Lowe and Kal Mann * Produced by Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise * 45: “Kissin’ Time” / “Nothin’ to Lose” * LP: Kiss * Label: Casablanca * Charts: Billboard (Hot 100 – #83)

“Kissin’ Time” (1974) – Kiss * Written by Bernie Lowe and Kal Mann * Produced by Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise * 45: “Kissin’ Time” / “Nothin’ to Lose” * LP: Kiss * Label: Casablanca * Charts: Billboard (Hot 100 – #83)

It’s too bad that no single Kiss song featured alternate lead vocals by all four members. They were all so distinctive. The closest they got was “Kissin’ Time,” the Bobby Rydell cover that Casablanca Records head Neil Bogart insisted they do in April ’74 to spark radio action. (Rydell’s record had reached #11 in 1959.) Loaded up with large market city references and kissing contest promotional possibilities (which indeed happened), Bogart mailed out 45s and then made certain the track would show up on July reprints of the debut album they had already released in February.

The track sported vocal turns by Gene, Paul and Peter and embarrassed the group, but it shouldn’t have. It preserved the huckstery chutzpah of the original, and Peter’s bum-bum-diddit drums in the verses suggested both Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song” and even cheeky Gene Krupa (“Disc Jockey Jump,” say). It also seems a tad appropriate that the introductory chart entry for the future lunchbox icons would have the sticky bubblegum residue of Neil Bogart—who’d brought the world “Yummy Yummy Yummy” and “Goody Goody Gumdrops”—all over it.