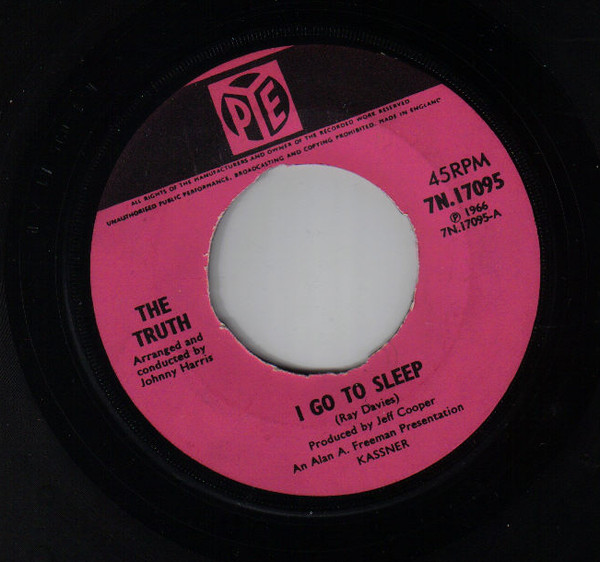

“Memphis Soul Stew” (1967) – King Curtis * Produced by Tommy Cogbill * 45: “Memphis Soul Stew” / “Blue Nocturne” * Label: Atco. Billboard Charts: Hot 100 (#33), Soul (#6).

A Texan he may have been, but sax man King Curtis comes off as a top Memphis ambassador on this record. The spoken intro tells us that the soul stew on special contains “half a teacup of bass,” a “pound of fatback drums,” “four tablespoons of boiling Memphis guitars,” a “little pinch of organ,” and “half a pint of horns.” These are musical ingredients, but I don’t know if there’s any better place to experience sound-taste synesthesia. The track gets you hungry.

The great bassist Jerry Jemmott, who played on the 1971 version for King Curtis’s Live at Fillmore West, writes in his Makin’ It Happen memoir about his disappointment that he couldn’t have been the one to have played on the 1967 single, a Top 40 hit. But Tommy Cogbill was the producer, and why would a bassist of that caliber need anyone else? (Cogbill’s involvement also reminds you how much more of a multiracial affair so many of the great Southern soul records actually were.)

But here’s why “Memphis Soul Stew” always finds its way back in my head: At the inevitable times when I realize a stressful situation will work itself out, or not kill anyone if it doesn’t, I hear King Curtis’s voice saying “this is gonna taste all right,” sometimes altered as “this is gonna be alright.”

The B-side is a notable contrast. The saxophone’s excused itself and everyone else sounds like they’ve had way too much stew.