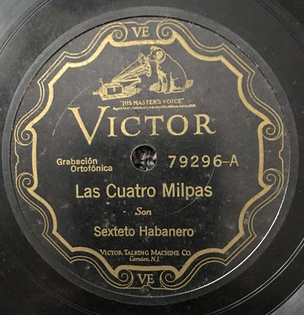

“Las Cuatro Milpas” (1927) – Sexteto Habanero * Written by Eduardo Vigil Y Robles * 78: “Las Cuatro Milpas” / “Mujeres Que Gozan” * Label: Victor

This, the most hypnotic of the earliest recordings of “Las Cuatro Milpas,” raises origin questions. The lyrics to a verse of it (the title of which translates to “the four cornfields”) appears as a “revolutionary song” in Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust (1939), sung by Earle the Mexican in the guise of a romantic song aimed at Faye Greener. It’s a song of longing for simpler, more abundant times, and it fits alongside that Hollywood novel’s themes of deception and upheaval. The three earliest recordings date to 1927: One by Cantantes de la Orquesta Tipica Mexicana (Victor), with only B. De Jesus Garcia credited as arranger; one by Magarita Cueto Y Juan Palido con The Castilians (Columbia), with only Eduardo Vigil y Robles credited as composer; and this one by the Cuban Son ensemble Sexteto Habaneros (Victor), with no one credited as composer. An online bio of Eduardo Vigil y Robles in Spanish identifies him as the music director of Latin American recordings at Victor between 1924 and 1929. Why, then, did the two Victor recordings not credit him as composer? And why are the lyrics to this Sexteto Habanero version different from the others?