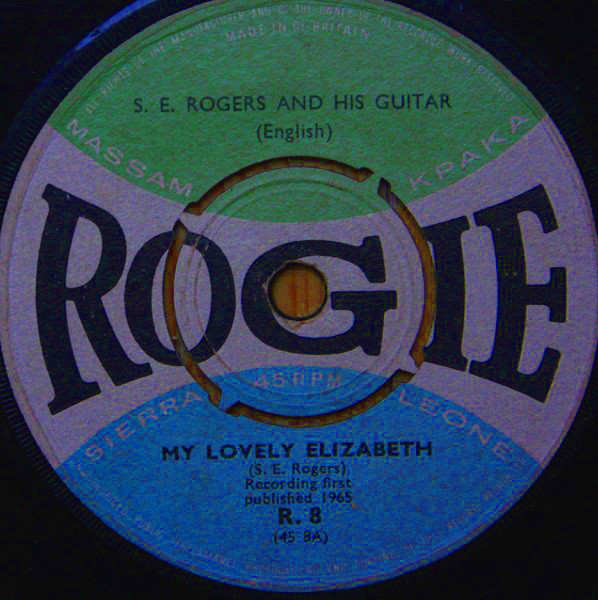

“My Lovely Elizabeth” (c. 1962) – S.E. Rogie and His Guitar* Written by S.E. Rogers * 45: “My Lovely Elizabeth” / “Advice to Schoolgirls” * Label: Rogie

Here’s an ideal representation of the West African “palm-wine” genre, so named for its suitability for having a nice tropical drink while you listen. Sierra Leone’s S.E. Rogie (Sooliman Ernest Rogers, d. 1994), in spite of the laid back impression his music conjures, was rather industrious, launching his own label in the early sixties and working its distribution. “My Lovely Elizabeth” was his first big seller – the label image above contains the frustrating note that it was “first published in 1965,” although other sources claim that the record had been floating around as early as 1962 and that his sound had changed quite a bit by 1965.

Here’s what Gary Stewart says in his Breakout: Profiles in African Rhythm (1992, p. 48): “Rogie’s biggest record of the early days was the 1962 hit ‘My Lovely Elizabeth’ … [it] sold an estimated thirteen thousand copies in Sierra Leone (an astonishing figure for the time given that record players were, for the most part, the property of more affluent city dwellers in a country whose population was largely rural) and thousands more when EMI picked it up for international distribution … Suspicious of EMI’s sales figures and disappointed in their royalty payments, he reverted to doing his own distribution.”

Side B contains Rogie’s “Advice to Schoolgirls,” in which he recommends, along with the virtues of honesty and staying true to one’s dreams, the avoidance of prostitution.