“Chilly Winds” (1971) – The Osmonds

an ever growing collection of short commentary on memorable tracks

“Sault Ste. Marie” (1971) – The Original Caste * Written and arranged by Bruce Innes * Produced by Roger Nichols * 45: “Sault Ste. Marie” / “When Love Is Near” * Charts: Canada #35

“Águas de Março” (1973) – João Gilberto * Written by Antonio Carlos Jobin * LP: João Gilberto * Label: Polydor

João Gilberto’s calm, singing-to-himself vocal delivery helped create a popular perception of Brazilian bossa nova as much as the compositions of Antonio Carlos Jobim did. Both men appeared on the 1964 hit album Getz/Gilberto, which also showcased American saxophonist Stan Getz and Gilberto’s then-wife Astrud. Throughout his career, Gilberto would pursue the ideal rendering of his “sound” while developing a difficult-artist reputation along the way. His manifesto of said sound may well be his 1973 self-titled album, which includes only voice, guitar, and spare percussion. The first song, a version of Jobim’s “Aguas de Marco” (the waters of March), turns like a pinwheel in a light afternoon breeze. The studio mic captures every micro-geometrical curve in Gilberto’s oral cavity, though, which is another way of saying that a little of this, for some listeners, may go a long way.

“Getting Over You” (1973) – Andy Williams * Written by Tony Hazzard * Produced by Richard Perry * UK 45: “Getting Over You” / “Remember (Andy Williams and Noelle)” * LP: Solitaire * Label: CBS * Charts: UK #35

With his Solitaire LP, Andy Williams shook things up a bit by getting in the studio with producer Richard Perry, who had been on a hot streak with hit albums by Carly Simon, Harry Nilsson, and Ringo Starr, among others. The song selection included deeper album tracks along with the usual hit covers, while Williams’s vocal now popped or swirled with new audio effects. The soft-rock flirtation, overall, brought forth three especially effective tracks: a version of George Harrison’s “That Is All,” which rescues it from the vocal-range issues of the former Beatle’s original, a version of Harry Nilsson’s “Remember,” featuring dreamy Nicky Hopkins piano (as did Nilsson’s original), and a song called “Getting Over You” by Tony Hazzard, a British songwriter who’d written some early hits for the Hollies (“Listen to Me”) and Manfred Mann (“Ha! Ha! Said the Clown”). How satisfying it must have been for him to hear his song done by one of pop music’s classic voices, with an arrangement full of such cascading instrumental payoffs (you need to listen all the way; Tom Hensley did these arrangements and took a lifelong gig with Neil Diamond thereafter). Hazzard himself had released a version of “Getting Over You” the same year, as did Hermans Hermits’ Peter Noone, but Williams’ was The One. Not released as a single in the US, it reached #35 in the UK with a B-side that included “Remember” revamped with shared vocals and dialogue with Williams’s daughter Noelle. (This all gets in the way of the sublime arrangement, so stick with the album version of that one.)

“Brown Eyed Handsome Man (TV version)” (1970) – Waylon Jennings * Written by Chuck Berry * Produced by Al Quaglieri * CD: The Best of the Johnny Cash TV Show 1969-1971 * Label: Columbia

The Johnny Cash Show celebrated the cross-pollination of American musical genres for two seasons between 1969 and 1971. Among the Man in Black’s guests were Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Ray Charles, the Monkees, and Derek and the Dominos. In January 1971, Waylon Jennings appeared with his then-current incarnation of the Waylors, a group whose various personnel all shared a strong Phoenix, Arizona connection. Because Jennings’s contract with RCA forbade him from using anyone but studio vets on his records, his live sound distinguished itself with an alternate edginess. While his late-1969 country chart hit version (#3) of Chuck Berry’s “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” trotted along tamely to Charlie McCoy’s harmonica, the 1971 TV version (link below) jangled and snapped to the rhythm of Jimmy Byrd’s twelve-string guitar, which looks like a double-neck Mosrite. An archived website alludes to double-necks that Byrd had developed by himself.

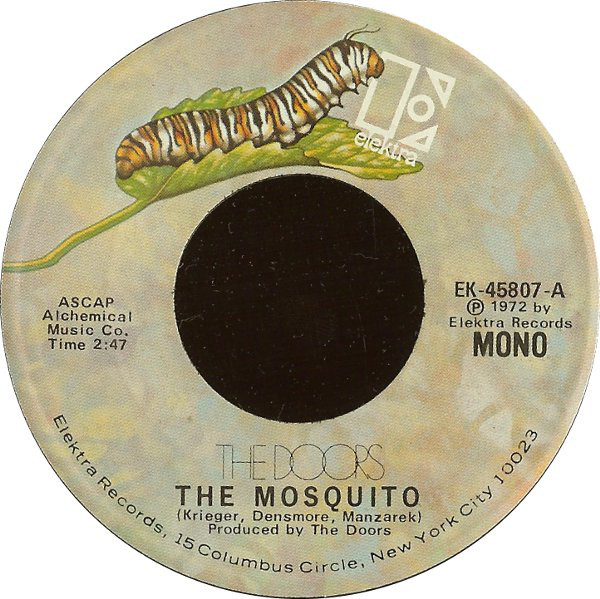

“The Mosquito” (1972) – The Doors * Written by Robby Krieger, John Densmore, and Ray Manzarek * Produced by The Doors * 45 B-side: “It Slipped My Mind” * LP: Full Circle * Label: Elektra * Charts: Billboard Hot 100 (#85)

Jim Morrison’s death in the summer of 1971 left the other three Doors with a glaring front-man vacancy, but they kept making music, including “The Mosquito,” a surprising borderline novelty hit. It wasn’t the single’s sales that registered surprise so much as the song itself, which had more in common with “La Cucaracha” than “Light My Fire.” Over a lightly engaged acoustic guitar, Robby Krieger mumbles for a mosquito to not bother him so he can eat his burrito, making way during the proceedings for two distinct instrumental interludes. One of these features Ray Manzarek’s organ, which overdoes it on the five-minute-plus LP version but bugs out mercifully on the under-three-minute 45. The single connected instantly with the international market, perhaps faster than any other Doors track. Before the year was over, cover renditions had begun sprouting up in Mexico, Spain, France, and beyond (none of which included the line about the burrito). Buyers of the Doors’ Full Circle album, incidentally, could enjoy the challenge of assembling a zoetrope included in the album packaging. Placed atop the record label, it would spin along at 33 1/3 rpm while showing a rudimentary animation of an evolving homosapien.

“All His Children” (1971) – Charley Pride with Henry Mancini * Written by Alan Bergman, Marilyn Bergman, and Henry Mancini * Produced by Jack Clement * LP: Sometimes a Great Notion (soundtrack) * 45 B-side: “You’ll Still Be the One * Label: Decca (LP); RCA (45) * Charts: #92 (Billboard Hot 100); #2 (Billboard country)

The 1971 Paul Newman film Sometimes a Great Notion (which had the much better overseas title of Never Give an Inch) put Ken Kesey’s Oregon logging novel to the big screen. If early seventies media tended to splash its feet in post-sixties cultural bewilderment, this film submerged itself, with every development—all the way to the closing credits—feeling like a gasping lunge through political and interpersonal complexity. Charley Pride’s forgettable theme song, written by composers who otherwise excelled in memorability, seemed to betray their low estimation of the country genre. The oddly-paired billing of Pride and Mancini (who gave the arrangement scoopfuls of stock background vocals) only added to the entire project’s murkiness. What makes “All His Children” special, though, is Pride’s final note, which sputters with knowing exasperation.

“Dawn” (1970) – Lovecraft * Written by Marty Grebb and Ken Wolfson * Produced by Lovecraft * LP: Valley of the Moon * Label: Reprise

After two albums, the psychedelic San Francisco-via-Chicago band H.P. Lovecraft, who had taken more than titular inspiration from the influential horror author, reinvented itself in 1970 as Lovecraft, with a personnel reshuffle bringing in former Buckingham Marty Grebb. Although their Valley of the Moon avoided the aural creepiness of their former incarnation, you could still detect a San Francisco rock hall vibe. The first section of the song “Dawn,” for example, borrows from the spacey, dangling guitar sound of pre-1970 Grateful Dead, with whom they’d shared the bill a time or two. Maybe the Dead’s Bob Weir took some inspiration from this song’s opening section for his distinctive “Playin’ in the Band” intro (introduced in 1971). Listen to the sequence at :43. “Dawn” can also be remembered for chiming in on Vietnam: “why do we fight this war of fools?”

“Can’t You Hear Me Knocking (Alternate Version)” (2015) – The Rolling Stones * Written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richard * CD: Sticky Fingers (Deluxe Edition) * Produced by Jimmy Miller * Label: Rolling Stones Records

Never released as an edited single, “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” became an album rock radio staple with its jagged guitar + Jagger vocal bursts. The song’s second section took shape as a four-minute jam, though, sounding like the kind of background incidental music earmarked for countercultural scenes in early seventies TV cop shows. (Featured soloists: Bobby Keys, Mick Taylor, and Billy Preston.) The 2015 deluxe edition of Sticky Fingers, finally, provides an official version of the track that shakes off the excess.

“It’s Forever” (1973) – The Ebonys * Written by Leon Huff * Produced by Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff * 45 B-side: “Sexy Ways” * LP: The Ebonys * Label: Philadelphia International Records * Charts: Billboard Hot 100 (#68); Billboard Soul (#14)

Among the jewels of early seventies Philly Soul, the Ebonys’ lesser known “It’s Forever” glitters with the best of them. The quartet originated in Camden, New Jersey, and built its sound on the interplay between the high tenor of David Beasley and the baritone of James “Booty” Tuten. They showed a flair for epic balladry similar to what the Dells were doing, with “It’s Forever” (written by Leon Huff) being their Exhibit A. The crucial, cascading vocal line that begins at :36 has since been sampled a time or two.