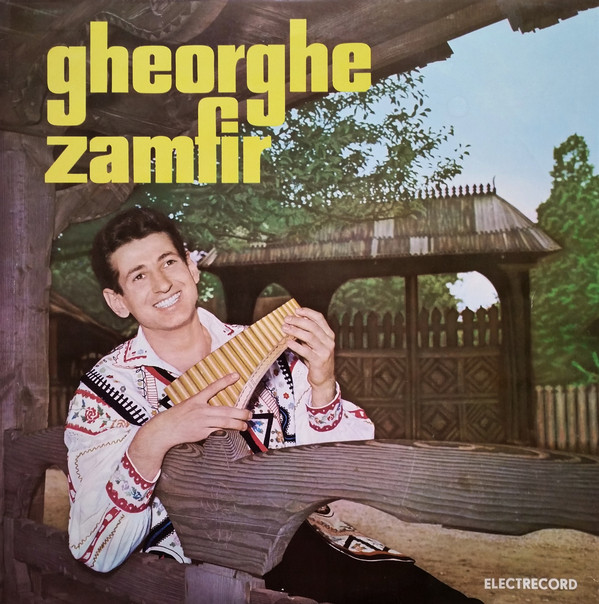

“Sîrba Bătrînească” (1966) – Gheorghe Zamfir * Traditional * LP: Gheorghe Zamfir * Label: Electrecord

Most Americans first learned of Romanian pan flute virtuoso Gheorghe Zamfir on a last-name only basis, when late ’80s TV commercials plugged him as a mood music maestro. Of course there was, and would continue to be, more to him than that, but the small screen does have a knack for making things smaller. The pan flute tradition in Romania, where the instrument is known as the nai, stretches back to the 1600s as a regular component among lăutari musicians (that term started out meaning lutists, but has come to signify a fuller folk spectrum). Zamfir’s first record, which the national label Electrecord released when he was 25, demonstrates an expressiveness in him that manages to animate an already lively musical idiom. The last track, “Sîrba Bătrînească” (the i in the middle of the second word is more commonly an a, but I’m going with the album cover), is a traditional 2/4 dance format with southern origins named after neighboring Serbia in the southwest. It’s a fast-tempo environment that circulates with frequency in Romanian folk, evoking scenes of unattended handcarts full of bell peppers and eggplants breaking free and rolling down steep hills. Zamfir is accompanied here by the Orchestra Florian Economu. After a few more records, he’d scale things down with a smaller band and fewer orthodox restrictions.