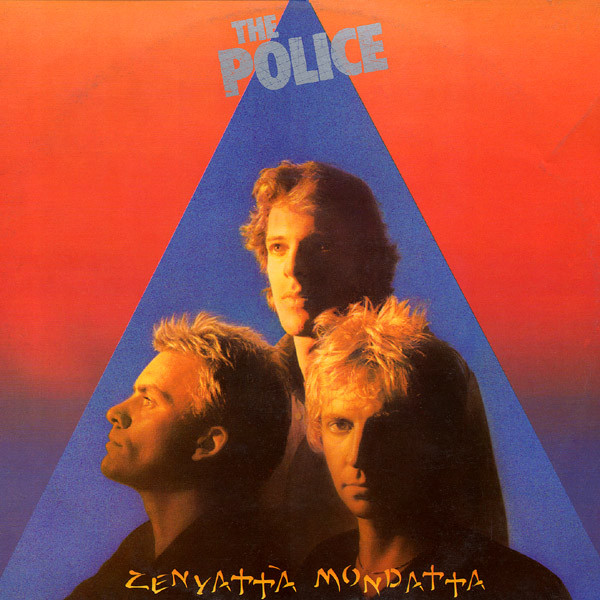

“Canary in a Coalmine” (1980) – The Police * Written by Sting * Produced by the Police and Nigel Gray * LP: Zenyatta Mondatta * Label: A&M

A song like this, where the singer expresses exasperation over someone’s environmental hyper-sensitivity, someone you imagine wearing a surgeon’s mask at the grocery store as standard practice, would have sounded woefully out of step only five years previous, when environmental consciousness still made for relevant pop music subject matter. Sting likely drew from Dave Edmunds’s 1977 cover of Bob Seger’s “Get Out of Denver” for the wordy Chuck Berry-like cadence in “Canary in a Coalmine,” an ideal match for their brand of sped-up ska. And what an appropriate source song, implying an exit from a fresh-air Rocky Mountain environment or an era where singers like John Denver used to sing about it.