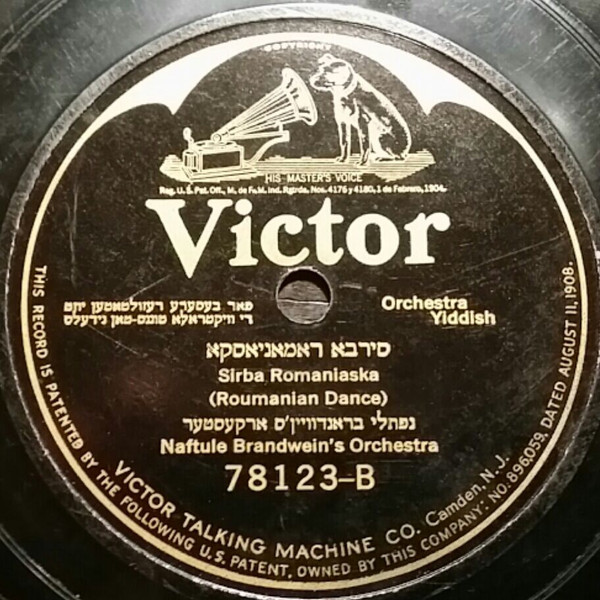

“Sirba Romaniaska” (1925) – Naftule Brandwein’s Orchestra * Traditional * 78: “Leben Zol Palestina”/ “Sirba Romaniaska” * Label: Victor

“Sirba Romaniaska” (1925) – Naftule Brandwein’s Orchestra * Traditional * 78: “Leben Zol Palestina”/ “Sirba Romaniaska” * Label: Victor

Clarinetist Naftule Brandwein’s 48 or so recorded tracks have become a series of blueprints for how klezmer, the traditional dance-friendly Jewish genre, ought to sound. Is this because he’s doing it “right” or because he plays with such listenable personality that he may as well be considered the authority? Brandwein came to the USA in 1908 from his home in Austrian Galicia, which would become part of Poland shortly thereafter, but is now part of the Ukraine. He knew enough songs from all over Eastern Europe that he could have claimed citizenship with any of the region’s ethnicities, from Romani to Romanian. This record, from the latter part of his whirlwind recording career in the 1920s, is called “Sirba Romaniaska,” with Sirba being the Romanian word for a fast dance associated with Serbia. The word “Romaniaska ” has its closest parallel to Ukranian, which testifies of Brandwein’s origins. On side A of this 78 is a track called “Long Live Palestine.” How do we assign any kind of idiomatic propriety to such festive ethnic goulash? (“Sirba Romaniaska” does not appear on Rounder’s 1997 roundup King of the Klezmer Clarinet.)