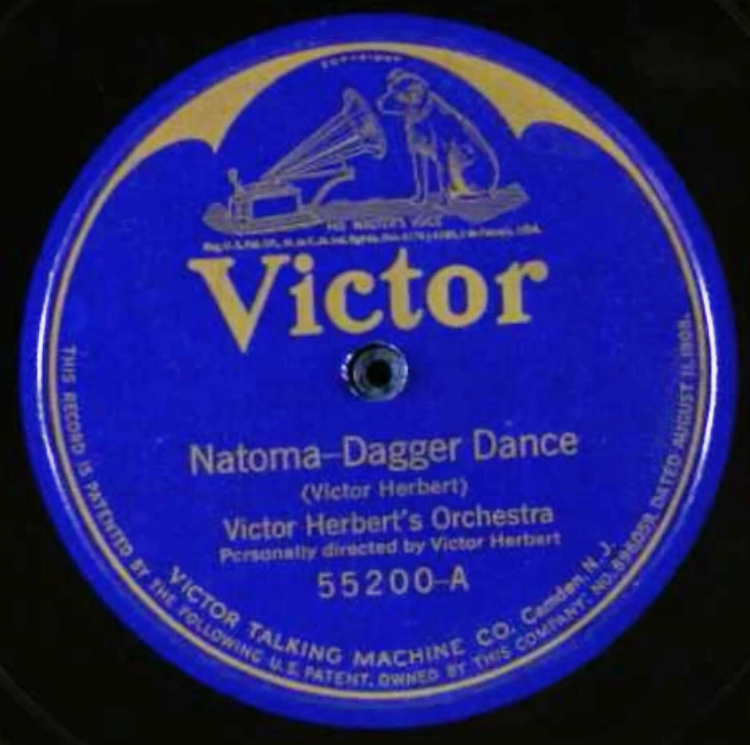

“Natoma-Dagger Dance” (1923) – Victor Herbert’s Orchestra * Label: Victor

More about the Hamm’s Beer “Land of Sky Blue Waters” theme: It uses the title, but nothing else, from a 1909 Charles Wakefield Cadmon song later recorded by the Andrews Sisters and others. Moira F. Harris, in her The Paws of Refreshment: The Story of Hamm’s Beer Advertising (2000), writes that the Minneapolis Campbell-Mithun ad agency devised it, with lyrics by Don Graewert and orchestration by Ernie Gavrin of WCCO radio.

Other influences included the lyrical cadence of Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, Haitian voodoo drumming, western movie soundtrack tropes, and the “dagger dance” from American light music composer Victor Herbert’s Natoma. Although operettas were Herbert’s forte, this was one of only two forays he made into grand opera, and it wasn’t a hit. With a libretto by Joseph D. Redding, it told the story of a Chumash maiden and her daughter, both of whom get tangled in situations with non-Chumash love interests in old Santa Barbara, California.

You can hear the Hamm’s Beer melody rolling around here, later to be tightened up into an unforgettable jingle aimed at football and baseball fans from the 1950s to the 1980s. You can also hear it near the beginning of “Natoma: Selections,” helpfully attended to by the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra for the Naxos American Classics series. The Orchestra, though, never attended to anything by Czech-American Rudolf Friml, whom several online sources credit erroneously as the composer of Natoma.