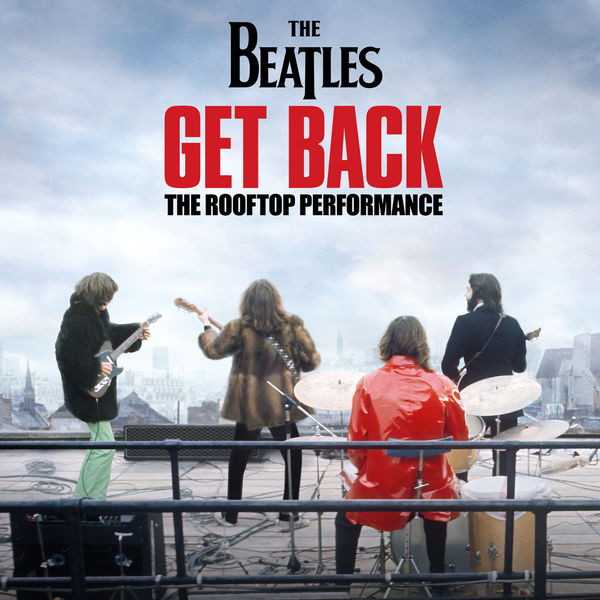

“Get Back (Rooftop Performance/Take 3)” (1969) – The Beatles * Written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney * LP : Get Back: The Rooftop Performance (2022)

Big Beatle rollouts, even momentous ones like Peter Jackson’s Get Back project, get more annoying with each passing year. This is thanks to the noisy social media theatre we’re locked inside of, where every moptopologist we know, along with everyone else, feels obligated to weigh in. (Case in point: what you’re reading. Although I did wait a full fourteen months.) Granted, they’re the world’s favorite group, but it feels like you can barely take something Beatle in on your own anymore without needing to close your eyes and shut your ears to spare yourself of people’s chatter.

So I watched Get Back, thought my own thoughts, marveled and observed, felt my internal download of the 1970 Let It Be film come apart and turn irrelevant, saw the dust fly off the prevailing narratives, witnessed songs take shape before my eyes, songs so familiar that I probably don’t ever need to listen to them again, and noted all the prismatic enhancement of the principals and their coterie that only ample footage can provide. But then came a part that although I knew was coming, nonetheless caught me off-guard in its extended form and got me all teary. It was the part when people on the street were given the opportunity to express how they felt about the Beatles.

“Once You Understand” (1972) – Lily Fields and the Family * Written by Lou Stallman and Bobby Susser * Produced by John Bennings * 45: “Once You Understand” / “Help Me Make It Through the Night” * Label: Spectrum

“Once You Understand” (1972) – Lily Fields and the Family * Written by Lou Stallman and Bobby Susser * Produced by John Bennings * 45: “Once You Understand” / “Help Me Make It Through the Night” * Label: Spectrum